Posted on: 10th October 2016 by Prof. Geoff Scamans

This week’s blog is a little bit different. It doesn’t describe our process improvement work, or an industry development. Instead we’re going to talk about art! Specifically, we’ll look at aluminium sculpture. Over to you Colin…

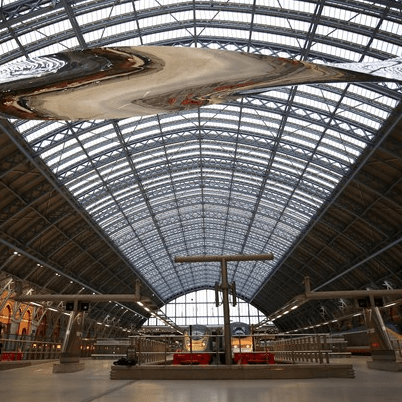

Aluminium sculpture at St Pancras

Earlier this year I passed through St Pancras train station in London on an unscheduled (thank you Easyjet) Eurostar trip back to the UK. Whilst there, a shimmering propeller reflecting distorted views of the station caught my eye. This was the aluminium sculpture Thought of Train of Thought (ToToT) by the designer Ron Arad.

It came about thanks to a partnership between St Pancras with the Royal Academy. Arad chose to create a calming installation of hypnotic movement in one of London’s busiest locations. It certainly took my mind off the cancelled flights and holiday insurance for a few minutes. Furthermore, the twirling reflections transfixed me and, just managing to avoid an inconveniently paced litter bin, I started to think about what had gone into creating ToToT.

Knowing a thing or two about aluminium probably gave me a head start. First of all ToToT is 18 metres long which is quite some size. However, movement makes it appear feather light. The structure is actually rib-reinforced, and it was made by a firm of former ship builders. The surface consists of aluminium sheets welded together and then polished to a mirror-like reflectivity.

If you haven’t had a chance to visit St Pancras, you can view the effect on the Royal Academy’s website.

Reflectivity

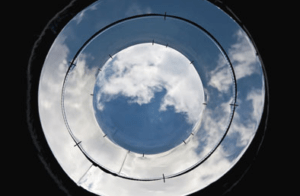

The reflective properties of aluminium will be well known to viewers of Channel 4’s Grand Designs. This programme often features light pipes as a means of providing light to rooms or spaces. Light pipes are large tubes that collect sunlight from outside. They then deliver it in an unadulterated form to rooms and hallways that don’t have any windows.

The theoretical limit on the efficiency by which aluminium can reflect light is about 92%. This is for the purest, smoothest form of the metal. However, to get up to the near 100% total reflectance found in the best light pipes, the producers apply nano layers of silver and silicon oxides.

At Innoval we use the change in total reflectance as a surface gets cleaner to measure the industrial cleaning process in aluminium plants. This is important for our customers who produce aluminium sheet for automotive applications. The cleanliness of the surface is critical to maintain the bonded strength of an aluminium structure. Furthermore, it enables the paint to look smooth and corrosion free over the vehicle’s lifetime.

Chemical attack

Getting back to aluminium sculptures, I can’t be alone in having the statue of Eros in Piccadilly, London, as the first memory of aluminium taught at school. “Unlike steel…” I can hear Mr Harris, my O level (that’s GCSE to anyone under 40) chemistry teacher say “…aluminium doesn’t rust”.

Looking back now I feel short changed by the Welsh Joint Education Committee’s curriculum. Of course, like Newtonian mechanics and evolutionary biology, there turned out to be a lot more to aluminium corrosion than the simple observation than it wasn’t the same as iron.

Some of my Innoval colleagues, who allegedly started their careers in aluminium just after Eros was erected in 1893, could have advised that siting the sculpture in an area badly affected by acidic fumes from urban life would have caused problems.

The protective layer of oxide that sits on the aluminium surface dissolves in acid. This is another fact used to great effect in the production of aluminium sheet. Acidic chemical etches clean millions of square metres of aluminium for end uses like beverage cans, caravans, printing plates and automotive sheet. However, this cleaning can also be accomplished with alkali solutions.

Incompatible materials

One of the attractions for using aluminium in the sculpture of Eros was its higher strength to weight ratio compared to bronze. As a result, the figure manages to balance on a very slender ankle while maintaining an extended arabesque.

Unfortunately, the most recent calamity to befall Eros was due to a different form of chemical attack to that described above. An alcohol fuelled miscreant decided to dangle from the minor god’s leg in 1990. The damage suffered may have been less if the infill inside the near pure aluminium outer shell had been of the same material. Instead, a previous repair used a lower melting point aluminium silicon alloy. The two materials did not bond well compromising the strength of the repair.

Colleagues at Innoval encounter these sorts of problems regularly in helping customers produce heat exchangers and welded products.

Who knew there’s more than one Eros?

Piccadilly Eros’s lesser known brother in Liverpool demonstrated another form of cleaning. A second casting of Gilbert’s famous statue appeared in Sefton Park in 1932 (you can read the story of the second Eros here). Unfortunately, this too suffered from extreme urban weathering which ate away whole sections of the aluminium sculpture.

Sterling work by Liverpool Museum’s conservation department restored the aluminium sculpture to its former glory. Part of this included laser cleaning to remove the hydrous oxide masking the surface.

We’ve looked at laser cleaning and pretreatment for industrial uses in the past and it’s shown some promise. Laser cleaning involves minimal environmental impact compared to chemical cleaning. Consequently, it’s a technology that may come to the fore in the future.

Joining challenges

Closer to Innoval’s home in Banbury we have our own aluminium sculpture. It stands as a monument to the town’s involvement with Northern Aluminium, Alcan, British Aluminium, Alcoa, and Sapa to name a few.

Though it lacks some elegance, the sculpture is a reminder of links to the production of Spitfires in World War II. Furthermore, it celebrates the success of aluminium in the automotive world. Just along the M40 motorway from Banbury, Jaguar Land Rover demonstrates this extremely well.

The joining challenges of putting Banbury’s aluminium sculpture together were similar to those faced by Jaguar’s engineers in the early 2000’s. They had to avoid using steel and aluminium in close contact as the galvanic couple causes a very rapid form of corrosion.

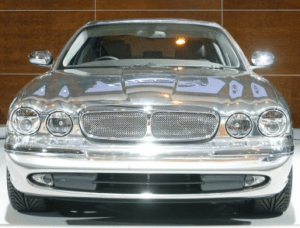

This could have been catastrophic given the number of rivets (3195) used in the original all-aluminium XJ. However, the engineers used coated rivets and, as you can see, they did a great job.

The future’s bright

Today the automotive industry continues to grasp the problems of global warming and the necessity to lightweight. Fortunately, the UK maintains a lead in aluminium research and lightweighting technology.

Recently, Brunel University’s 50th Anniversary saw the unveiling of the final piece of sculpture in this post. Design company Artem created a sculpture, which is entitled ‘Connect’, figure 8. However, the students at Brunel University came up with the original idea for it.

‘Connect’ consists of five inward facing characters, with a space for a sixth character. Interestingly, the sculpture invites visitors to become a part of it by standing in the gap and holding hands with the adjacent characters. You can read the full story here.

Constellium, which is a partner in the new Advance Metals Casting Centre at Brunel University, sponsored the sculpture. We also work closely with Brunel in developing casting technology for 21st century lightweighting.

Finally, we are able to help with your lightweighting project if you need us to. The Innoval team has contributed to the development and industrialisation of much of the automotive sheet technology in use today. We have been working with OEMs and sheet, casting and extrusion suppliers on automotive lightweighting technology for many years.

This blog post was originally written by Dr Colin Butler who has now left the company. Please contact Prof Geoff Scamans if you have any questions.